Issues

In a few years, the system of private research funding in France has shifted from a system dominated by subsidies (80% subsidies, 20% taxation in 2000) to a tax incentive system in 2015 (opposite proportions).

The French research tax credit (RTC) system is now well established in France and is the subject of major debates and annual evaluations, given its cost (€ 5.6 billion). While many studies have demonstrated its effectiveness, this key instrument for the competitiveness and attractiveness of the French territory is today heavily challenged by many countries.

Countries with tax incentives for R & D (Deloitte)

Developing and justifying an incentive system is complex: it must be tailored to each country’s economy, industry and tax system. The European Commission’s latest proposal on the CCCTB (Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base) includes a European “super-deduction” for innovation and research, which demonstrates the importance of tax incentives to support private R&D activities.

Global overview of aid systems

Most countries implement tax incentives and subsidies, with varying allocations and modalities:

- Subsidies are mainly used to help actors to develop and manage a strategy and a joint project, which cannot be carried out by each of them, and to support the development of ad hoc infrastructures, often in the context of projects of societal interest (transportation, health, etc.).

- Tax incentives are more individual in nature, and automatic triggers are more effective.

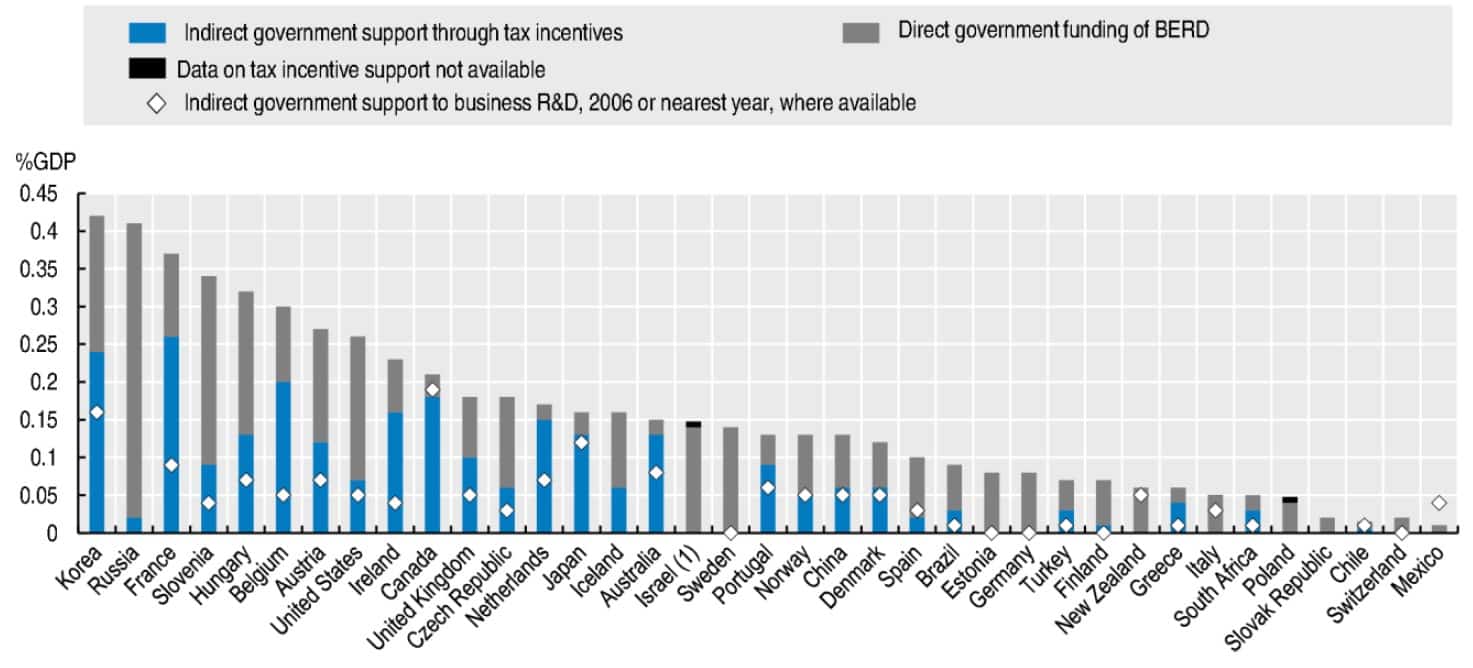

Volume and distribution of incentives for R&D (OECD study)

There are several categories:

- Countries with strong direct support for R&D projects: Korea, Russia, France, Slovenia, Hungary, Belgium and the United States

- Countries where the intervention is mainly of a tax nature: France, Belgium, Canada, Ireland, Netherlands, Japan and Australia

- Countries reluctant to tax incentives: Germany, Sweden, Norway, Estonia … which are not the least performant in terms of R&D.

In view of the first 5 countries of the above classification, it is clear that diametrically different options are used: even within the same geographical area (the United States, Canada or Europe), the options are also radically opposed, reflecting as many national particularities.

Everything is then a question of degree and national strategy, deployed on 3 axes:

- Subsidies require a significant amount of drafting and negotiation by companies, while the selection and management of files also represent a significant cost to the State. Thus, the length of investigation is a source of additional time in increasingly competitive innovation systems. Moreover, the method of selecting a priori projects which will be subsidized by the State or other public funding bodies is to entrust to the State (rather than to companies) the choice of technologies of the future.

- The OECD, in a recent study, agrees that the tax incentives for innovation are more effective: the main risk is taken by the company that mostly finances the project, chooses the technological directions for the future according to its strategy.

- Support for market development is also critical to the success of projects. These indirect supports can take many forms: reserved or specific purchases of innovation by the administration, platforms and facilities for experimentation, etc.

Conclusion

There is no magic formula nor universal remedy for innovation and growth, and each country has developed its own strategy according to its history, economy, structure and population.

The French scheme is nowadays a relevant system in view of the very high level of taxation, global economic stagnation and industrial regression observed for more than 15 years.

Deloitte’s annual study outlines these different variants for all countries in the world, and gives companies the opportunity to improve the effectiveness of their financing, based on their existing and future presence, and assisted by local experts.